Lexington home to variety of cultural, authentic restaurants

BY Haley Pierce

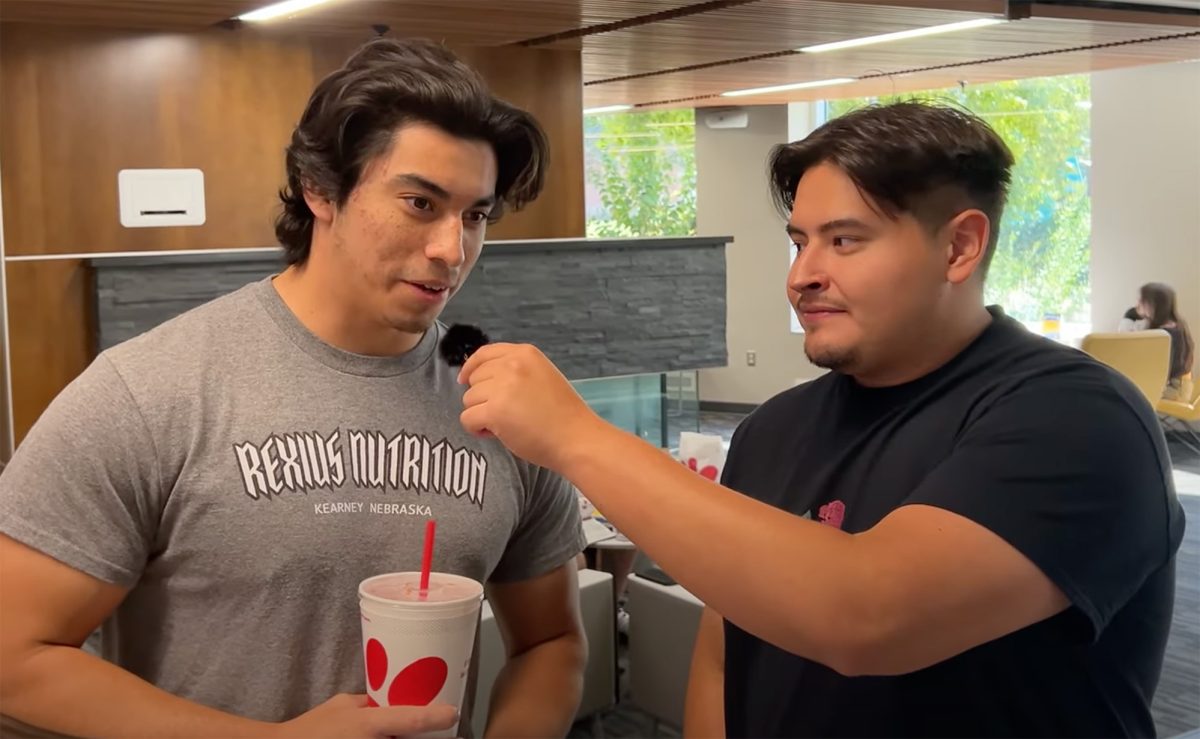

“It’s not Kool-Aid,” Carlos Gutierrez says with a laugh while handing me a pineapple, or piῇa, Raspado. And it’s not. At Ruby’s Raspados, the Kool-Aid flavoring of a snow cone is replaced with the sweetness of a thick syrup.

Raspados are the traditional Mexican version of a shaved ice, but the difference doesn’t end with the syrupy flavor. “The ice is a lot thicker,” Gutierrez says, “It has to hold the thicker syrup.” Indeed, the ice is closer to crushed ice than snow, and layered on top of it is a sweet syrup made from fresh fruit, pieces of fresh fruit, and perhaps even candy.

The raspado stand tries to use the freshest fruit possible for its drinks, even if it means searching a distance away. “Sometimes it’s Texas, sometimes it’s California, sometimes it’s the HyVee in Kearney,” Gutierrez explains with a smile.

While not so common in Nebraska, raspado stands are scattered across the southwest. Though, not all raspado stands are created equal. The task of finding fresh fruit and the effort of making homemade syrups is what leads most raspado stands to modify the traditional recipes explains Gutierrez. But not at Ruby’s. “Everything we do is the traditional recipe,” Gutierrez says.

Customers will find eight traditional raspado flavors, including piῇa, limon, coco, fresa, vanilla, tamando, mango, and guayaba. Gutierrez says the mango is very popular, and so is the vanilla with white American customers. In addition, Ruby’s serves up six specialty drinks.

It’s a Saturday afternoon in early fall, and the trailer for Ruby’s Raspados is parked in the gravel lot of Lexington’s sale barn. Gutierrez’s twin boys – Jedediah and Jeremiah – are playing out front. They are 6 years old and identically dressed. While their dad is serving up raspados, I talk to them about school. They are all smiles as they tell me they “really like math class.”

For Gutierrez, the raspado business is only naturally a family affair. The business was passed down to his family from his wife’s. Now, Gutierrez’s eldest son runs the raspado stand; Gutierrez only fills in when his son is busy. “I wish I could do this full time,” he says.

Jedediah and Jeremiah are giggling when Leah Dutro pulls up.

Dutro wastes no time ordering two Megamango Locos. The specialty drink features not only fresh mango, but chili and sour punch straws. “It’s weird, but somehow it just works,” Dutro says. She is a nurse at the hospital, and she and her coworkers discovered Ruby’s Raspados after a late night shift some number of years ago. Now, Dutro, makes regular visits to the raspado stand.

But Ruby’s Raspados isn’t the only location in town Dutro dines at regularly. She and her family moved to Lexington about 20 years ago, and she has had some time to find her favorite restaurants. Standing in the parking lot, she spins in a circle – pointing to restaurants and describing the best dish at every one.

“You can’t forget fruit guy,” she says. Fruit guy? She doesn’t know his name, but he’s at the park almost every weekend – slicing and dicing the freshest fruit (and sweet corn) one can find.

I drive to the park in search of fruit guy. I can’t find him, but I take the opportunity to sit on a bench and finish my raspado. It’s sunny, but the park seems unusually busy for a day so late in the season. Entire families are at the park – moms and dads with their little kids and their teenagers too. There is a big laugh from the playground as I leave to find some of the eateries Dutro told me about.

The town of Lexington is home to about 10,000 people according to the 2010 census and over 20 ethnic restaurants and bakeries. Many of these restaurants are owned and operated by members of Lexington’s immigrant community – a community with people from Mexico, El Salvador, Somalia and Guatemala according to City Data and Data USA.

This cultural diversity is evident in the food. “Some of these restaurants are better known for the basics while others are known more for their cultural delicacies,” Erin Green, a UNK student from Lexington said. One such restaurant known for culturally specific food is El Rinconcito.

Situated along fourth street, Papuseria El Rinconcito serves up traditional Salvadoran eats, including papusas. A papusa is a thick tortilla dough filled with cheese, pork, beans or any combination of the three. It’s then fried and served alongside vegetables and red salsa.

Berta Recinos opened the papuseria in 1999, alongside her daughter Carla. Recinos greets me at the door. We’ve never met, but our handshake more closely resembles a hug. She tells me how she and her daughter sold papusas to students outside of school after sports practice before quickly moving to their first restaurant location on Highway 30.

“Pepto Bismol pink” Recinos says through laughs as she recalls the color of the original building. Recinos’ family moved to Lexington in 1988 her daughter Julia explained, and at the time of its opening, Recinos’ pink papuseria was just one of two ethnic restaurants in town.

However, while the food was good, El Rinconcito didn’t always attract non-Hispanic customers. “They were scared they’d walk in there, and nobody would speak English,” Julia said. So, in 2017, El Rinconcito relocated to fourth street and a former flower shop. “Now, white Americans, the Chinese, even Somalians come in,” Julia added.

Indeed, food is one way culture is shared in Lexington. “It amazes me how individuals of different cultures can come together just by placing food on the table,” Green said. “We can gather to eat in family owned and operated restaurants offering amazing, culturally-specific food and all enjoy different parts of the meal but come away with a new respect for the culture,” she added.

And at El Rinconcito, the sharing of culture doesn’t end with the food. Berta Recinos runs the restaurant with her husband Enrique, who has taken it upon himself to decorate the new location.

The lower half of the walls are covered in wood paneling – paneling that Enrique has carved and painted with parakeets, flowers, and a sunrise. “He does it all by hand” Julia said.

Green sees how food is used to introduce people to other cultures. “Really, food is the bridge between cultures in Lexington,” she said.

This link between food and culture might be part of the reason the restaurant owners take such pride in their businesses. Recinos explains excitedly how the health department not only always gives her business passing marks but it always adds praise for the cleanliness and orderliness of her papuseria.

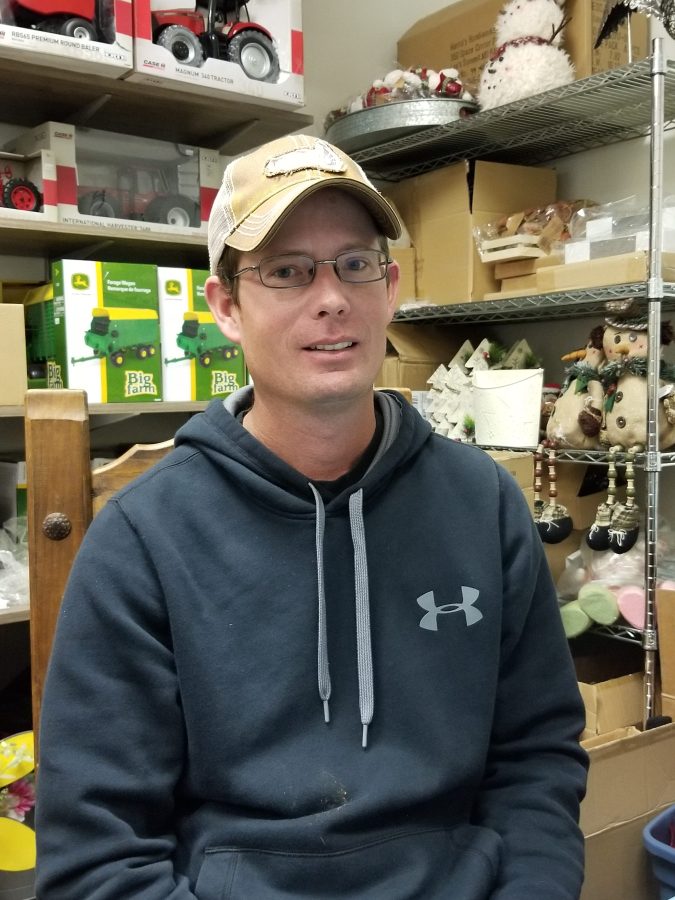

Just down the street at La Vasquez Market, a similar pride in one’s work can be found. “To own my own business – that’s the dream,” says Gerardo Vazquez.

He opened the grocery store in 2000, and three years ago, he expanded his business into the next-door restaurant by opening a meat market. Now, he and his eldest daughter run the store, Vazquez said. But the family ties don’t end there. Throughout the store, pictures of Vazquez and his children at soccer games are hung proudly. One of his youngest daughters runs about.

Again, the sharing of culture is evident at the market. Papel picados – perforated paper décor – hangs from the ceiling. Vazquez is also stocking products from Mexico and Central America. “There’s a lot of different people,” Vazquez says of Lexington’s population, adding he tries to serve them all. At La Vazquez Market, one can find goods from Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Cuba, and more recently, Somalia explained Vazquez.

Serving these populations extends beyond placing products on shelves too. La Vasquez Market is the type of place where a poster hangs on the wall as a “cheat sheet” for calculating the exchange of the Honduran Lempira into the U.S. Dollar. It’s also the kind of place where posters hang on the wall that read “Gracias a nuestros clientes,” or “thank you to our customers” with pictures from opening day – Augosto 12, 2000.

As I’m leaving the grocery store, I notice choco bananos – chocolate covered frozen bananas. I mention that a friend has told me how great they are. Vasquez’s daughter hands me two. They won’t let me pay.