Thomas Jefferson said, “If I had to choose between government without newspapers, and newspapers without government, I wouldn’t hesitate to choose the latter.”

As a young journalist, I’m glad the third U.S. president supports my career field. But I truly understood his mindset in the fall of 2020, when COVID-19 hit. I received a lesson in the truth — not everyone tells it, or at least not all of it.

I was unfamiliar with the pandemic, so naturally, I tried to avoid the topic at all costs. But journalists don’t always get to choose their topics.

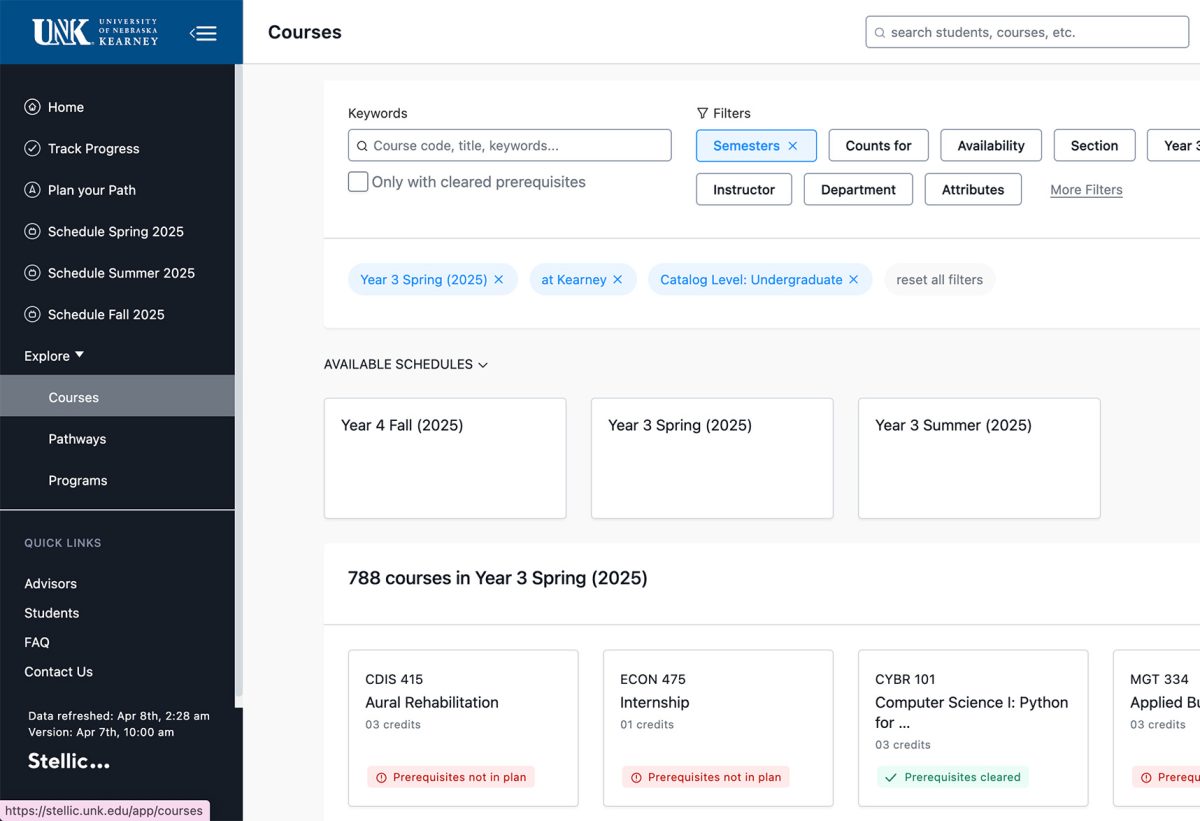

I interviewed Residence Life about the resources available to quarantined or isolated students on campus. I thought it was easy enough. I called the university officials and asked them about the process, and quarantine sounded pretty nice.

According to a university official, students got gift baskets when they arrived at their isolation rooms, their toilet paper was replaced and food was delivered to their doors.

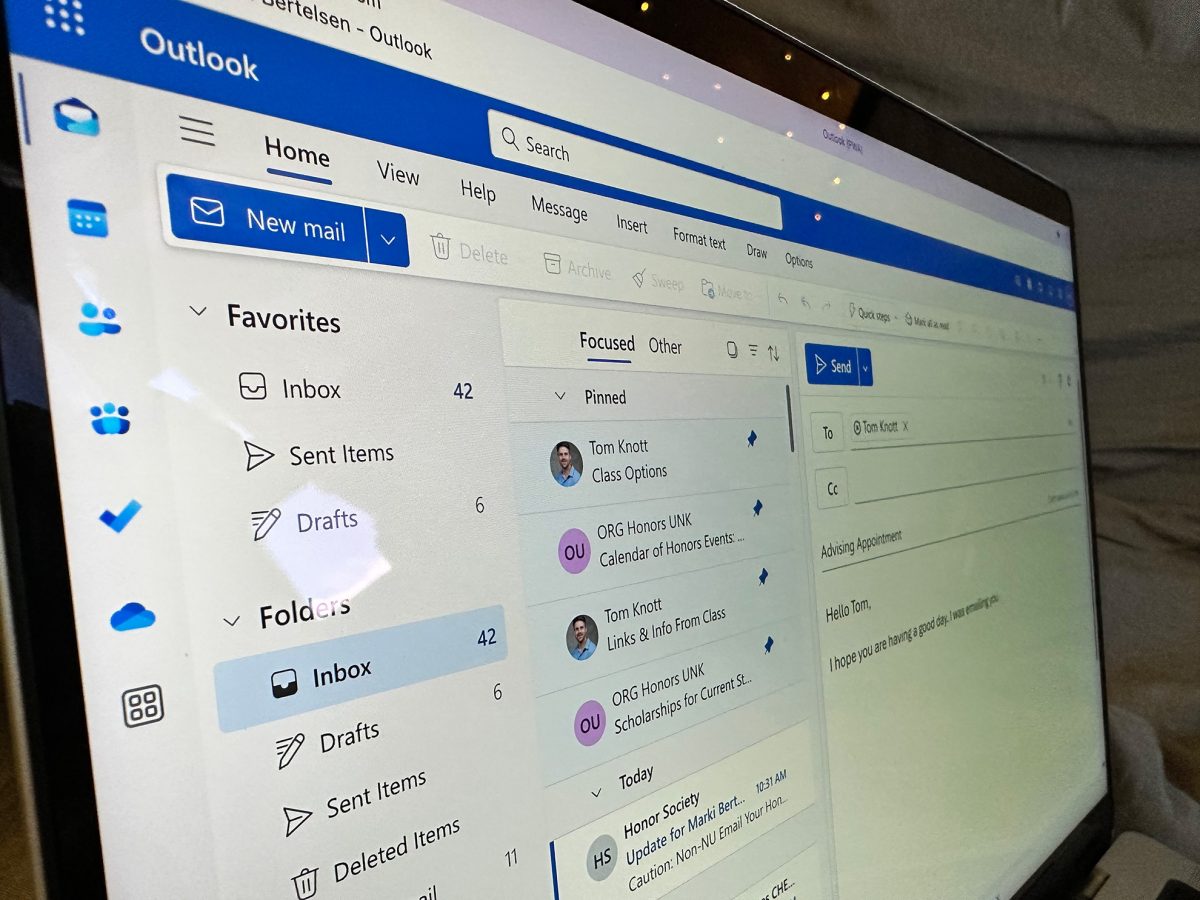

The article was published with no problem, until a fellow reporter mentioned students who had opposite experiences. At the time, my newspaper adviser would critique each issue’s articles in front of the class. I felt a knot in my stomach as he picked mine apart.

After hearing about the quarantined students, my adviser suggested I investigate the untold side of the story. He knew I was a better writer than that.

My adviser was the first to tell me the truth. I should not have let my lack of confidence hold me back from reporting about COVID-19. It was laziness and naivety that caused me to focus on what university officials told me, instead of focusing on who The Antelope newspaper is meant for — the students.

Besides UNK Athletics, the Nebraskats swing choir was the first group that was quarantined before fall classes even started. A member was not feeling well during training and tested positive for COVID-19.

A series of unfortunate events took place, such as miscommunication from Student Health and promises that were not kept by Residence Life. When I brought these claims to UNK officials, they admitted to the mistakes and discussed plans of improvement.

The swing choir members and the director did not hold any information back. If I hadn’t told their story, no one would have even known about the swing choir’s bad experiences.

My intentions were not to paint the unversity in a bad light, however. The SPJ Code of Ethics prioritizes minimizing harm as a journalist’s duty. I love UNK and many of the officials, but it was a truth that needed to be told so the quarantine/isolation experience could be improved moving forward.

The swing choir members were grateful for my work, and I experienced so much relief after covering all the bases. Still, I was not proud of the article because it was a way to redeem my shoddily-written first article.

When it came time to submit entries for the Golden Leaf Awards, a fellow editor insisted on entering the Nebraskats article. Despite my refusal, he submitted it anyway.

I’m grateful he had faith in me because the article won the general news category. Writing about the Nebraskats’ poor experiences was a humbling feat, but the quarantining and COVID-19 tracing process became more refined throughout the semester. That student group just happened to be the first guinea pigs UNK tested their COVID-19 procedures on.

Journalists are meant to serve the community. They keep officials in check, translate the facts, clear up confusion and use their skills to improve communities — not tear them apart.