ANTELOPE EDITORIAL

In the 17th and 18th century, the privilege of earning a university-level education was one that was reserved only for the elite. Famous lawyers and politicians were among the chosen few that were able to receive higher education. They were only able to do so in schools that are now seen as Ivy-Leagues such as Princeton and Dartmouth.

With the beginning of the 20th century, came what many people revere as an “educational revolution” in which women, people of color, and those who were once considered “the common man” could now receive an education and better their future just as well as anyone rich or higher-up.

Today, much more is being taught in schools than just liberal arts and Latin. But how much progress have schools actually made when comparing the education received and the cost? Personally, I feel that this push to move into an educated world has caused universities to lose much of what once made them havens for the intellectual.

There was once a time when money could buy you knowledge that few other people possessed. Today, colleges re-teach us high school information or require $100 textbooks to explain research found on the internet.

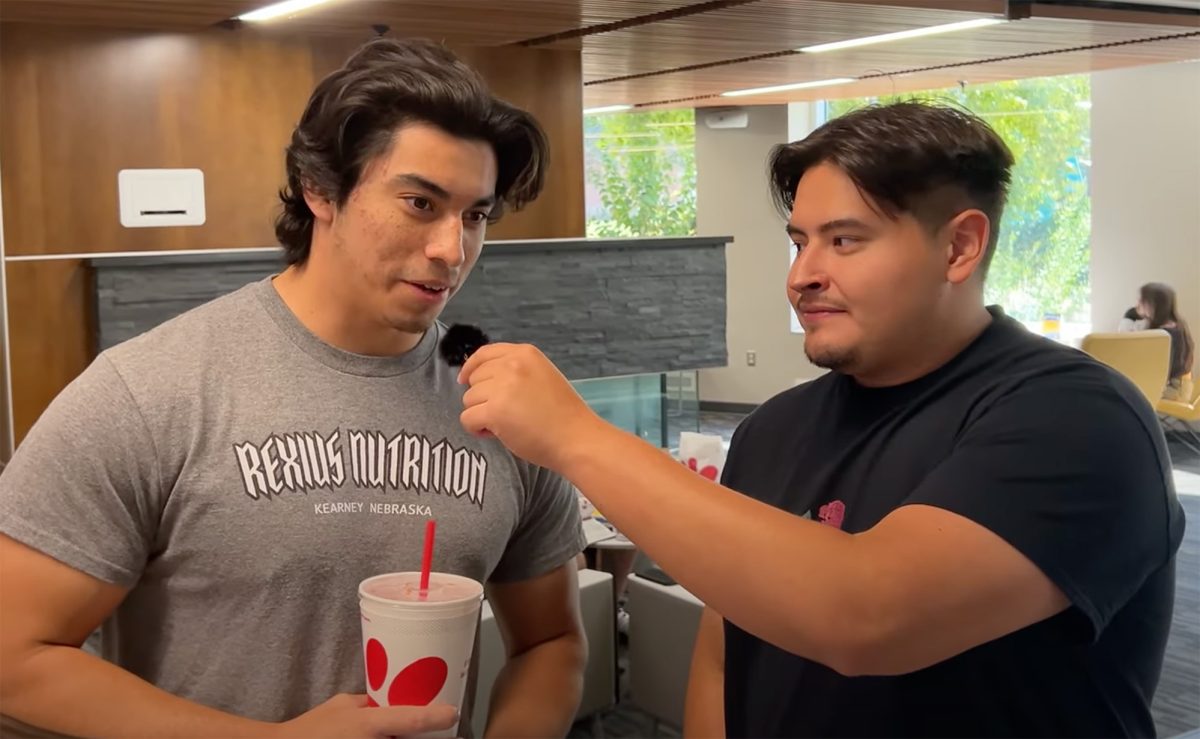

Have you ever wondered why Nebraska universities require a minimum ACT score of 21 when your friend who scored an 18 received the same “You’ve Been Accepted” letter that you did?

Money.

The students with lower grades and test scores that want so desperately to receive a higher education typically have to take more intro-level classes than those who enter college with high GPAs and dual-credit classes on their transcript. These students have to spend an extra few hundred dollars to catch up to the students that studied for the ACT. That money ends up in the pocket of the university.

Colleges are far from the intellectual hubs we imagine them to be. Students don’t sit around and discuss what they’ve learned in class or the current political state of the nation. They talk about how late they stayed up to finish a paper and how they might award themselves through partying.

Today, colleges are in “the business of education” as Constantine Papadakis said in a 2006 interview with Gallup. Papadakis, the president of Drexel University, has increased the profit of Drexel tenfold since being hired in 1995.

Despite the fact that nearly all colleges are non-profit organizations, Papadakis said that this does not mean that universities are not money-driven. In fact, he encourages it, saying that without a drive for profit, universities are doomed. In his opinion, Drexel University is a one-billion-dollar corporation, in the business of ensuring that their “customers” leave feeling that they have purchased an education that is worth the money spent.

Drexel also admits that when looking through applicants, the university looks not only at the academic achievement of a future student, but also their ability to afford the cost of education.

I value my education. Within the next two years I will become the first person in my family to receive a four-year degree. Knowing that I wouldn’t have been able to accomplish this a century ago proves that as a population, the value of producing educated generations is important.

However, I see high-income families with star-athlete children receiving acceptance letters to Yale and Harvard, and I cannot help but feel discontent with the thought that I would never be able to afford a school like that.

While higher education, I believe, is realistically tangible to anyone who wishes to receive it, we all know that not all degrees are created equal. The name at the front of your degree and the color of your tassel at graduation is a direct representation of how much money you spent to get here. The fact of the matter is that far fewer graduates from Princeton walk away with a useless degree, and a minimum wage job than the number of those from UNK who have accepted this as the way things are.

I am not saying that all students should have an equal opportunity to be accepted to an Ivy League school. In fact, I am saying the exact opposite. Big-name schools, though they maintain a high price-tag, have the luxury of producing only the best education. Yet, sadly the same cannot be said for the rest of the universities in the nation.

At the beginning of the 20th century, fewer than 1,000 schools existed. Today, that number is higher than 5,300- each one with a similar price tag, yet all with a far different educational standard. It is clear that the value of education in the United States is glossed over and viewed as pristine, but it lies behind a curtain of people who wish to profit.