Faculty, students and community members discuss history need for, effectiveness of protests

Jessie Turek

Antelope Staff

Dr. Lorna Bracewell, her wife Paula and Dr. William Aviles could have just turned around on their drive to the Women’s March in Omaha. They debated during much of the car ride about whether or not it mattered at all that they were participating in marches happening all over the country.

Dr. Aviles, smiled while reminiscing about the road trip experience and recalled: “They almost dropped me off the side of the road…because I was, I don’t know about this!”

But the other passengers were firm: “No, keep going!”

Dr. Bracewell and Dr. Aviles wanted the engaged audience at the April 7 Fireside Chat to look at political resistance and protests from a variety of different viewpoints.

Aviles, the political science professor, asked, “What do you guys think about when you think about a protest? In your minds a protest is achieved with what?”

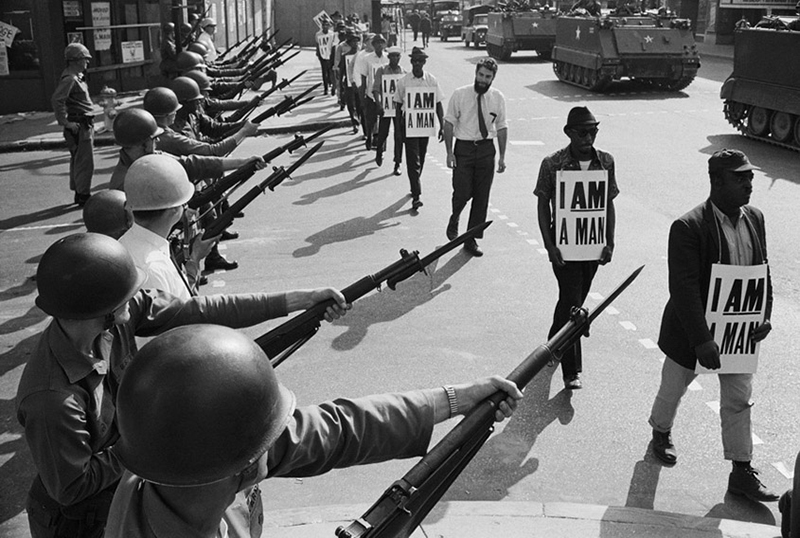

Civil rights protestors walked a dangerous path.

Attendees’ ideas of protest included signs with catch phrases and songs like rap that pump up and communicate the message they are trying to convey, building solidarity. Achievements through protests are thought to start a conversation on the topic and involve a level of commitment that is significantly higher, with risks involved audience members said.

The Emerging Politics of Resistance, facilitated by assistant professor Dr. Lorna Bracewell and professor Aviles of the political science department, focused on the effectiveness of the different forms to voice opinions available in democratic citizenships.

The topic for the Chat was chosen in response to protests happening around the country since President Trump’s inauguration protests in January

Aviles said, “One of the biggest motivations for us to organize this event, in terms of his inauguration, was the Women’s March that took place there. Estimating between 3 to 5 million people across the country came out in protest, absolutely unprecedented numbers that showed up to D.C .the day after his inauguration.”

The Feb. 16 Day without Immigrants, March 8 Women’s March and different immigration protests brought back shades of the famous protest movements of the sixties. Aviles said, “There are political scientists and sociologists that are tracking this information down and assessing this that has been pretty unprecedented.”

When Dr. Bracewell asked how many in the room had participated in a protest of any kind around half raised their hands.

Her question, “Do you think it mattered?” spurred varied audience remarks.

The majority nodded their head in agreement.

Dr. Bracewell then asked, “Why?”

Associate Professor Dr. Claude Louishomme, also in the political science department, recalled protests from his past that did have a lasting effect: “My sister and I went to Washington, DC a year after Ronald Reagan was elected along with 800,000 others to put pressure on the president make Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday a holiday, and Ronald Reagan had a horrible civil rights record. He did sign that off. I think that march in freezing January did make a difference along with other stuff.”

Another reason for organized protest shared by a community audience member, Andrew White, was the tiresome and ineffective response of being told to write to congressmen about problems. White agreed that, however, writing can sometimes make a difference. “The problem lies in if the writing becomes just a chainmail and the message is not always received by the leaders. There is more attention given when leaders start seeing you on the news, out there actively participating,” White said.

Dr. Bracewell said some instances, like Dr. Louishomme’s experience had a direct, visible effect. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday became a holiday. But gauging effectiveness is not always that simple when a demand made by a protesting group is not as clear.

One attendee viewed the Woman’s March protest as being narrowed to a focus of fear about women’s rights under attack, instead of a direct, clear message as seen in the civil rights protest or Vietnam protest.

Another found the Day without Immigrants’ protest to show the measurable daily labor impact without immigrant workers, showing how much they contribute to their communities.

In the discussion about the impact of protest movements, Aviles and Bracewell talked about data they found interesting in their research regarding the civil rights marches, which show how opinions of protests have changed over time.

Aviles said, “There are some surveys from the 1960s. You think about the civil rights marches, MLK’s ‘I Have a Dream’ and right now, historically, we are like, ‘Wow! Those protests were phenomenal, and we look at how effective they were.’ Well, there was a real difference in opinion in particular from white respondents in the United States.

“However,” Aviles said, “The reaction to protest sometimes changes over time.”

The survey from 1966 asked poll participants, “Do you feel the demonstration by Negroes on civil rights have helped more or hurt more in the advancement of civil rights?”

Dr. Aviles said, “I was probably surprised it was such a dramatic majority of whites were just convinced that it hurt. And that’s just a few years after that particular march.” The data from the Roper Center showed 85 percent of white respondents said the march hurt, with only 15 percent agreeing it helped.

He added, “Obviously there was a difference in African-American respondents.” Data from 1969 showed 70 percent of African-Americans found the march to help with only 14 percent thinking it hurt.

Although the impact of recent citizen protests cannot be measured for complete effectiveness yet, past protests have shown they can make a major impact.