liermanm2@lopers.unk.edu

The Platte River has underpinned life across south-central Nebraska since before the written record. When drought and low snowmelt make water scarce, anxieties around how to use water rise as tough decisions must be made.

According to population estimates from Jeff Buettner of the Central Nebraska Public Power and Irrigation District, “well over 1 million people” in Nebraska, representing over half of the state’s population of 1.9 million people. The state’s human and wildlife populations rely on human management of the river to ensure it’s able to consistently support them — even when the river would otherwise run dry.

The Platte’s fate is shared by all those that depend on it.

“Looking at the future, climate modeling predicts that it’s going to get warmer,” said Jason Farnsworth, executive director of the Platte River Recovery Implementation Program. “Some models say there’s going to be more precipitation, and some say there’s going to be less precipitation, but all of them sort of indicate it’s going to be less snowpack and more big flood events. What you could see is less year to year supply and more intermittent supply where you don’t have enough, and then often you have too much.”

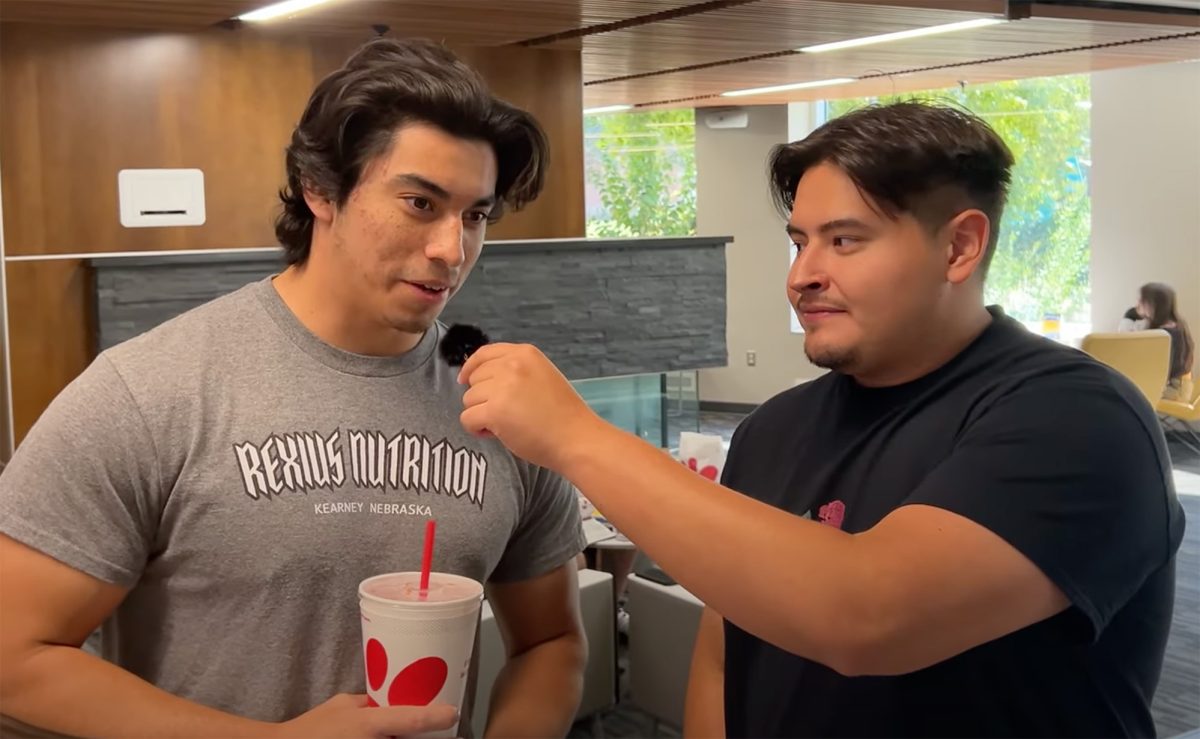

Farnsworth is one of several speakers scheduled to present this week as researchers and other river stakeholders meet in Kearney for the Nebraska Water Center’s Platte River Basin Conference from Oct. 24-27.

In addition to Farnsworth, four UNK professors, including Vijendra Boken, Mary Harner, Melissa Wuellner and Pricila Iranah are scheduled to speak at the conference.

“We try to come at the science from as many different perspectives and disciplines as possible,” Farnsworth said. “If we’re learning basically the same thing from every direction, it gives our decision makers confidence that we’re learning something useful.”

With elections two weeks away, neither of Nebraska’s gubernatorial candidates have water planning as part of their official platform though the winner will inherit the controversial Perkins County Canal project. In addition, the early portion of the next governor’s term will almost certainly have to address the delayed impacts of current drought conditions. As of Oct. 18, drought conditions affected most of the state according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Based on Google trends data, the number of Nebraskans searching for information using the search term “drought” is on an upward trend from its current 57% share of historical interest. Search activity peaked in January 2013 after steadily increasing through one of the most acute drought years in recent memory during 2012. Before that, the dry spell of the early 2000s proved to be especially difficult for the system.

If conditions improve in the short term, plans and lessons taken from this period will still be required for responding to future threats to the system’s balance.

“The early 2000s was bad enough that it almost broke the system, so we know how to cope under those conditions,” Farnsworth said. “If [this drought] is worse than the drought of the early 2000s, the big question is, ‘All right, are we improving our management quickly enough to offset that?’ I guess necessity is the mother of invention.”

Photos by Kristen Wetovick and Mitchell Lierman / Antelope Staff