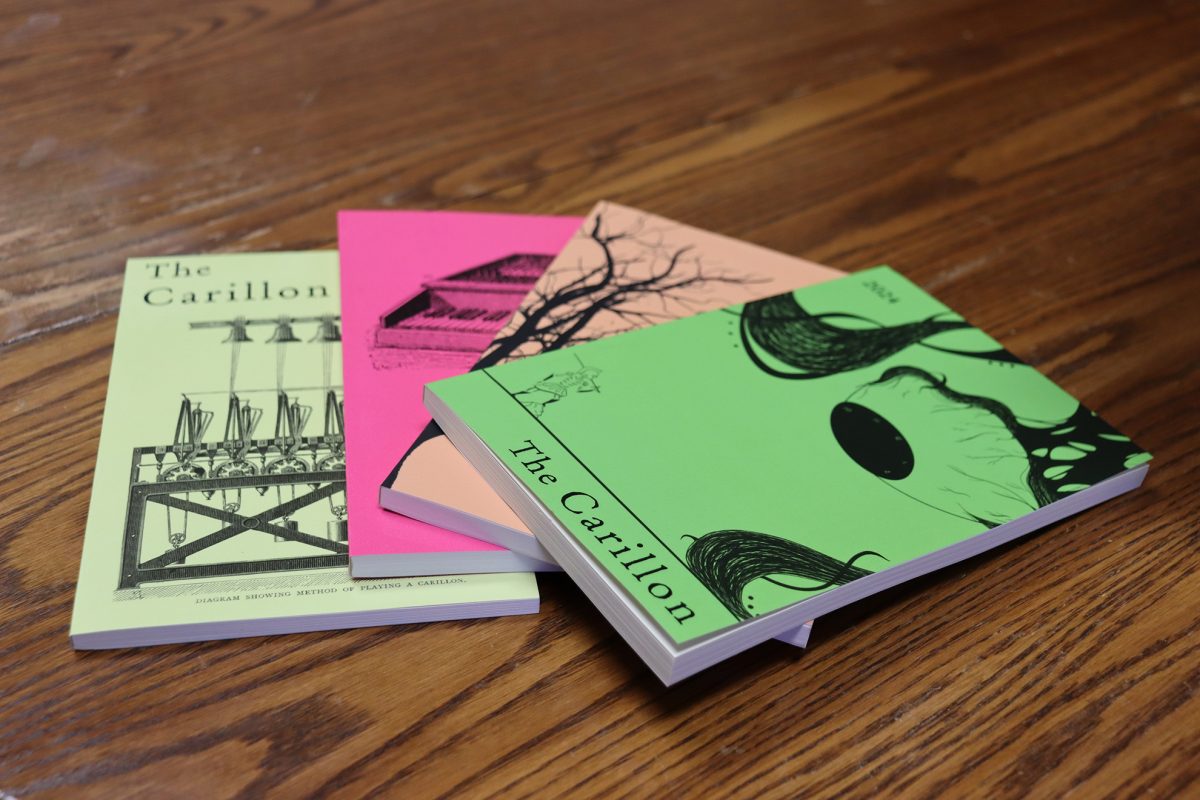

By Mitchell Lierman

The first bombs fell in Kyiv just as I was saying goodbye to my friends over the phone.

For a moment, I was in disbelief. The next, I had a tab open on every news outlet I know.

That first night, the dorm lounge transformed into an absurdist gallery to watch.

People came in and out, looking on with an uncertain and melancholic malaise before either shuffling back to their room or joining the husks still glued to the screen. Their eyes were on a TV that one student hauled out of their room and daisy-chained to their laptop in a string of dongles that might have been funny at any other time.

A girl from upstairs returned after a while, unable to sleep and looking for company.

“I couldn’t sleep, and I knew you were running your situation room down here,” she said.

In the wry, sarcastic tone she delivered it, it had every right to garner at least a short breath of ironic appreciation.

The uneasy, jokey reminder that most of us are eligible for a military draft was a near constant, however unlikely the odds.

The joke normalized so quickly, and why wouldn’t it?

We were inundated with a 24/7 supply of 15 second TikToks and constant pleas into the horrible voids of Twitter, Facebook and Reddit. It was a narrative that we were primed to accept as the world stood with bated breath watching the crisis, like watching a trailer for a movie no one wanted to see.

People compared and pondered, argued and questioned. To those of us who have lived in this perpetual noise machine for all of our teenage years, none of it was new. And despite the horror of it all, people lived their lives. Because what else could they possibly do?

As nuclear holocaust loomed in the 1960s, communication theorist Marshall McLuhan coined the term “global village” to describe the phenomenon of global media consumption as our narratives converged.

A trending item is the Ghost of Kyiv, a rumored fighter pilot said to have shot down six Russian fighters. Another is Volodymyr Zelenskyy, the comedian who played the president on TV before Ukrainians elected him. Not to mention, “Russian boat, go **** yourself,” the famous reply from the Ukrainian troops on Snake Island when a warship demanded they surrender. These stories, true or not, are modern myths that took the internet by storm.

It is horrifying and mesmerizing all at the same time to live in this global era of media. In an age where fewer people die every year from war than at any other time in human history, the existential reminders of poverty, disease and war serve to humble us and plead for our compassion.

In this numbing storm of ideas that dominates our lives, we cannot give in to apathy.

But neither can we sacrifice our souls to a media machine bent on putting a price tag on every ad that runs after each video of a little girl in unicorn pants being dragged bloody and dying from the back of an ambulance deep in Kyiv. The balance is trying, but necessary.

This time challenges us to become better members of our global village and to work on the problems we in the hopes that we will leave the world better for others who share it with us. We must stop looking endlessly into the past and step inchingly forward into an uncertain and unpromised future.

This is the purpose of education.

We cannot waste our chance.